Calling Convention

To allow separate programmers to share code and develop libraries for use by many programs, and to simplify the use of subroutines in general, programmers typically adopt a common calling convention. The calling convention is a protocol about how to call and return from routines. For example, given a set of calling convention rules, a programmer need not examine the definition of a subroutine to determine how parameters should be passed to that subroutine. Furthermore, given a set of calling convention rules, high-level language compilers can be made to follow the rules, thus allowing hand-coded assembly language routines and high-level language routines to call one another.

In practice, many calling conventions are possible. We will use the widely used C language calling convention. Following this convention will allow you to write assembly language subroutines that are safely callable from C (and C++) code, and will also enable you to call C library functions from your assembly language code.

The C calling convention is based heavily on the use of the hardware-supported stack. It is based on the push, pop, call, and ret instructions. Subroutine parameters are passed on the stack. Registers are saved on the stack, and local variables used by subroutines are placed in memory on the stack. The vast majority of high-level procedural languages implemented on most processors have used similar calling conventions.

The calling convention is broken into two sets of rules. The first set of rules is employed by the caller of the subroutine, and the second set of rules is observed by the writer of the subroutine (the callee). It should be emphasized that mistakes in the observance of these rules quickly result in fatal program errors since the stack will be left in an inconsistent state; thus meticulous care should be used when implementing the call convention in your own subroutines.

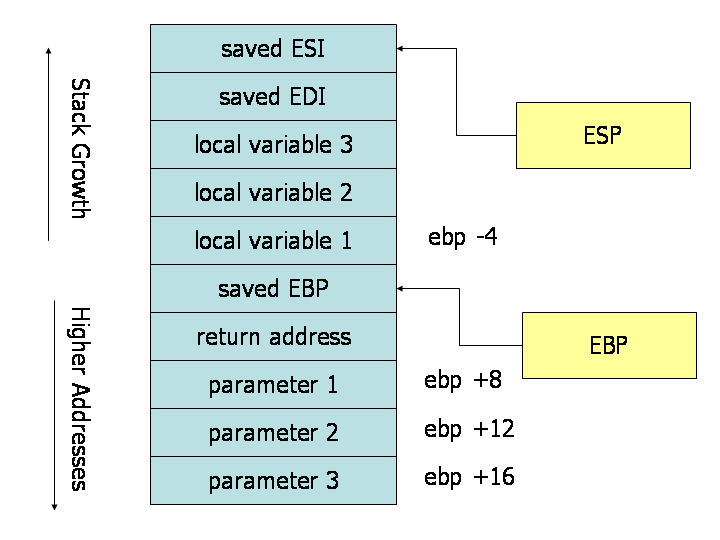

A good way to visualize the operation of the calling convention is to draw the contents of the nearby region of the stack during subroutine execution. The image above depicts the contents of the stack during the execution of a subroutine with three parameters and three local variables. The cells depicted in the stack are 32-bit wide memory locations, thus the memory addresses of the cells are 4 bytes apart. The first parameter resides at an offset of 8 bytes from the base pointer. Above the parameters on the stack (and below the base pointer), the call instruction placed the return address, thus leading to an extra 4 bytes of offset from the base pointer to the first parameter. When the ret instruction is used to return from the subroutine, it will jump to the return address stored on the stack.

Caller Rules

To make a subrouting call, the caller should:

Before calling a subroutine, the caller should save the contents of certain registers that are designated caller-saved. The caller-saved registers are EAX, ECX, EDX. Since the called subroutine is allowed to modify these registers, if the caller relies on their values after the subroutine returns, the caller must push the values in these registers onto the stack (so they can be restore after the subroutine returns.

To pass parameters to the subroutine, push them onto the stack before the call. The parameters should be pushed in inverted order (i.e. last parameter first). Since the stack grows down, the first parameter will be stored at the lowest address (this inversion of parameters was historically used to allow functions to be passed a variable number of parameters).

To call the subroutine, use the call instruction. This instruction places the return address on top of the parameters on the stack, and branches to the subroutine code. This invokes the subroutine, which should follow the callee rules below.

After the subroutine returns (immediately following the call instruction), the caller can expect to find the return value of the subroutine in the register EAX. To restore the machine state, the caller should:

Remove the parameters from stack. This restores the stack to its state before the call was performed.

Restore the contents of caller-saved registers (EAX, ECX, EDX) by popping them off of the stack. The caller can assume that no other registers were modified by the subroutine.

Example

The code below shows a function call that follows the caller rules. The caller is calling a function _myFunc that takes three integer parameters. First parameter is in EAX, the second parameter is the constant 216; the third parameter is in memory location var.

push [var] ; Push last parameter first

push 216 ; Push the second parameter

push eax ; Push first parameter last

call _myFunc ; Call the function (assume C naming)

add esp, 12

Note that after the call returns, the caller cleans up the stack using the add instruction. We have 12 bytes (3 parameters * 4 bytes each) on the stack, and the stack grows down. Thus, to get rid of the parameters, we can simply add 12 to the stack pointer.

The result produced by _myFunc is now available for use in the register EAX. The values of the caller-saved registers (ECX and EDX), may have been changed. If the caller uses them after the call, it would have needed to save them on the stack before the call and restore them after it.

Callee Rules

The definition of the subroutine should adhere to the following rules at the beginning of the subroutine:

Push the value of EBP onto the stack, and then copy the value of ESP into EBP using the following instructions:

push ebp mov ebp, espThis initial action maintains the base pointer, EBP. The base pointer is used by convention as a point of reference for finding parameters and local variables on the stack. When a subroutine is executing, the base pointer holds a copy of the stack pointer value from when the subroutine started executing. Parameters and local variables will always be located at known, constant offsets away from the base pointer value. We push the old base pointer value at the beginning of the subroutine so that we can later restore the appropriate base pointer value for the caller when the subroutine returns. Remember, the caller is not expecting the subroutine to change the value of the base pointer. We then move the stack pointer into EBP to obtain our point of reference for accessing parameters and local variables.

Next, allocate local variables by making space on the stack. Recall, the stack grows down, so to make space on the top of the stack, the stack pointer should be decremented. The amount by which the stack pointer is decremented depends on the number and size of local variables needed. For example, if 3 local integers (4 bytes each) were required, the stack pointer would need to be decremented by 12 to make space for these local variables (i.e., sub esp, 12). As with parameters, local variables will be located at known offsets from the base pointer.

Next, save the values of the callee-saved registers that will be used by the function. To save registers, push them onto the stack. The callee-saved registers are EBX, EDI, and ESI (ESP and EBP will also be preserved by the calling convention, but need not be pushed on the stack during this step).

After these three actions are performed, the body of the subroutine may proceed. When the subroutine is returns, it must follow these steps:

Leave the return value in EAX.

Restore the old values of any callee-saved registers (EDI and ESI) that were modified. The register contents are restored by popping them from the stack. The registers should be popped in the inverse order that they were pushed.

Deallocate local variables. The obvious way to do this might be to add the appropriate value to the stack pointer (since the space was allocated by subtracting the needed amount from the stack pointer). In practice, a less error-prone way to deallocate the variables is to move the value in the base pointer into the stack pointer: mov esp, ebp. This works because the base pointer always contains the value that the stack pointer contained immediately prior to the allocation of the local variables.

Immediately before returning, restore the caller's base pointer value by popping EBP off the stack. Recall that the first thing we did on entry to the subroutine was to push the base pointer to save its old value.

Finally, return to the caller by executing a ret instruction. This instruction will find and remove the appropriate return address from the stack.

Note that the callee's rules fall cleanly into two halves that are basically mirror images of one another. The first half of the rules apply to the beginning of the function, and are commonly said to define the prologue to the function. The latter half of the rules apply to the end of the function, and are thus commonly said to define the epilogue of the function.

Example

Here is an example function definition that follows the callee rules:

.486

.MODEL FLAT

.CODE

PUBLIC _myFunc

_myFunc PROC

; Subroutine Prologue

push ebp ; Save the old base pointer value.

mov ebp, esp ; Set the new base pointer value.

sub esp, 4 ; Make room for one 4-byte local variable.

push edi ; Save the values of registers that the function

push esi ; will modify. This function uses EDI and ESI.

; (no need to save EBX, EBP, or ESP)

; Subroutine Body

mov eax, [ebp+8] ; Move value of parameter 1 into EAX

mov esi, [ebp+12] ; Move value of parameter 2 into ESI

mov edi, [ebp+16] ; Move value of parameter 3 into EDI

mov [ebp-4], edi ; Move EDI into the local variable

add [ebp-4], esi ; Add ESI into the local variable

add eax, [ebp-4] ; Add the contents of the local variable

; into EAX (final result)

; Subroutine Epilogue

pop esi ; Recover register values

pop edi

mov esp, ebp ; Deallocate local variables

pop ebp ; Restore the caller's base pointer value

ret

_myFunc ENDP

END

The subroutine prologue performs the standard actions of saving a snapshot of the stack pointer in EBP (the base pointer), allocating local variables by decrementing the stack pointer, and saving register values on the stack.

In the body of the subroutine we can see the use of the base pointer. Both parameters and local variables are located at constant offsets from the base pointer for the duration of the subroutines execution. In particular, we notice that since parameters were placed onto the stack before the subroutine was called, they are always located below the base pointer (i.e. at higher addresses) on the stack. The first parameter to the subroutine can always be found at memory location [EBP+8], the second at [EBP+12], the third at [EBP+16]. Similarly, since local variables are allocated after the base pointer is set, they always reside above the base pointer (i.e. at lower addresses) on the stack. In particular, the first local variable is always located at [EBP-4], the second at [EBP-8], and so on. This conventional use of the base pointer allows us to quickly identify the use of local variables and parameters within a function body.

The function epilogue is basically a mirror image of the function prologue. The caller's register values are recovered from the stack, the local variables are deallocated by resetting the stack pointer, the caller's base pointer value is recovered, and the ret instruction is used to return to the appropriate code location in the caller.